Chain of Responsibility

Intent

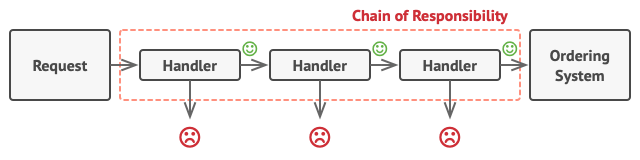

Chain of Responsibility is a behavioral design pattern that lets you pass requests along a chain of handlers. Upon receiving a request, each handler decides either to process the request or to pass it to the next handler in the chain.

Problem

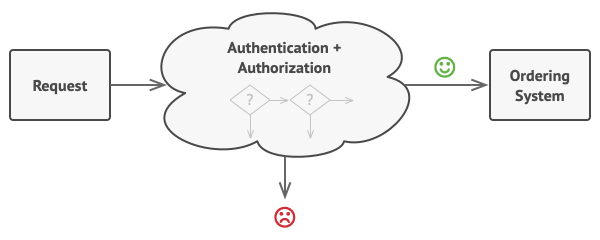

Imagine that you’re working on an online ordering system. You want to restrict access to the system so only authenticated users can create orders. Also, users who have administrative permissions must have full access to all orders.

After a bit of planning, you realized that these checks must be performed sequentially. The application can attempt to authenticate a user to the system whenever it receives a request that contains the user’s credentials. However, if those credentials aren’t correct and authentication fails, there’s no reason to proceed with any other checks.

The request must pass a series of checks before the ordering system itself can handle it.

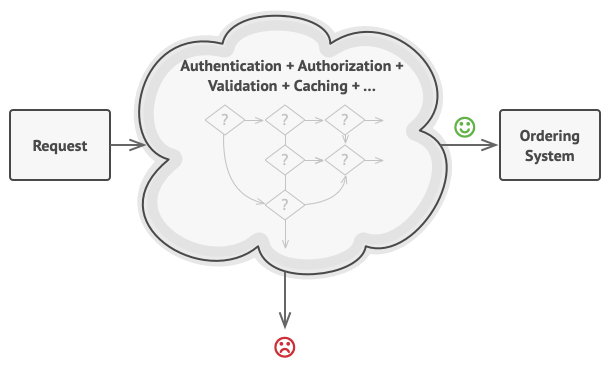

During the next few months, you implemented several more of those sequential checks.

-

One of your colleagues suggested that it’s unsafe to pass raw data straight to the ordering system. So you added an extra validation step to sanitize the data in a request.

-

Later, somebody noticed that the system is vulnerable to brute force password cracking. To negate this, you promptly added a check that filters repeated failed requests coming from the same IP address.

-

Someone else suggested that you could speed up the system by returning cached results on repeated requests containing the same data. Hence, you added another check which lets the request pass through to the system only if there’s no suitable cached response.

The bigger the code grew, the messier it became.

The code of the checks, which had already looked like a mess, became more and more bloated as you added each new feature. Changing one check sometimes affected the others. Worst of all, when you tried to reuse the checks to protect other components of the system, you had to duplicate some of the code since those components required some of the checks, but not all of them.

The system became very hard to comprehend and expensive to maintain. You struggled with the code for a while, until one day you decided to refactor the whole thing.

Solution

Like many other behavioral design patterns, the Chain of Responsibility relies on transforming particular behaviors into stand-alone objects called handlers. In our case, each check should be extracted to its own class with a single method that performs the check. The request, along with its data, is passed to this method as an argument.

The pattern suggests that you link these handlers into a chain. Each linked handler has a field for storing a reference to the next handler in the chain. In addition to processing a request, handlers pass the request further along the chain. The request travels along the chain until all handlers have had a chance to process it.

Here’s the best part: a handler can decide not to pass the request further down the chain and effectively stop any further processing.

In our example with ordering systems, a handler performs the processing and then decides whether to pass the request further down the chain. Assuming the request contains the right data, all the handlers can execute their primary behavior, whether it’s authentication checks or caching.

Handlers are lined up one by one, forming a chain.

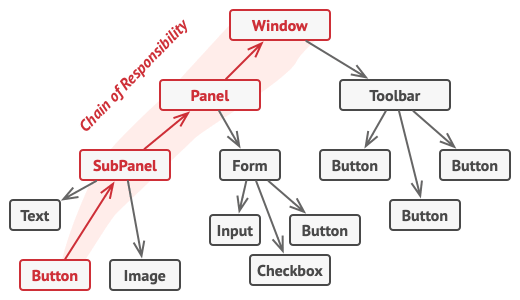

However, there’s a slightly different approach (and it’s a bit more canonical) in which, upon receiving a request, a handler decides whether it can process it. If it can, it doesn’t pass the request any further. So it’s either only one handler that processes the request or none at all. This approach is very common when dealing with events in stacks of elements within a graphical user interface.

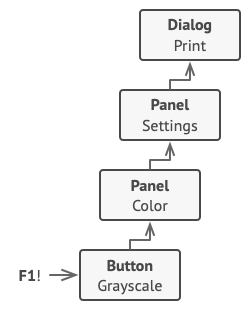

For instance, when a user clicks a button, the event propagates through the chain of GUI elements that starts with the button, goes along its containers (like forms or panels), and ends up with the main application window. The event is processed by the first element in the chain that’s capable of handling it. This example is also noteworthy because it shows that a chain can always be extracted from an object tree.

A chain can be formed from a branch of an object tree.

It’s crucial that all handler classes implement the same interface. Each concrete handler should only care about the following one having the execute method. This way you can compose chains at runtime, using various handlers without coupling your code to their concrete classes.

Real-World Analogy

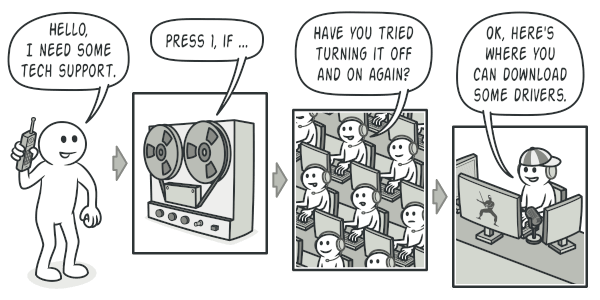

A call to tech support can go through multiple operators.

You’ve just bought and installed a new piece of hardware on your computer. Since you’re a geek, the computer has several operating systems installed. You try to boot all of them to see whether the hardware is supported. Windows detects and enables the hardware automatically. However, your beloved Linux refuses to work with the new hardware. With a small flicker of hope, you decide to call the tech-support phone number written on the box.

The first thing you hear is the robotic voice of the autoresponder. It suggests nine popular solutions to various problems, none of which are relevant to your case. After a while, the robot connects you to a live operator.

Alas, the operator isn’t able to suggest anything specific either. He keeps quoting lengthy excerpts from the manual, refusing to listen to your comments. After hearing the phrase “have you tried turning the computer off and on again?” for the 10th time, you demand to be connected to a proper engineer.

Eventually, the operator passes your call to one of the engineers, who had probably longed for a live human chat for hours as he sat in his lonely server room in the dark basement of some office building. The engineer tells you where to download proper drivers for your new hardware and how to install them on Linux. Finally, the solution! You end the call, bursting with joy.

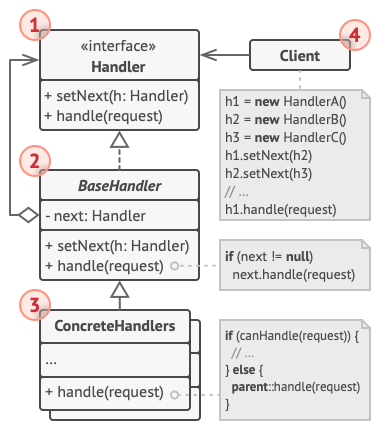

Structure

-

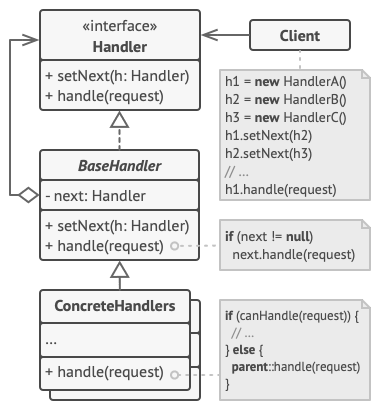

The Handler declares the interface, common for all concrete handlers. It usually contains just a single method for handling requests, but sometimes it may also have another method for setting the next handler on the chain.

-

The Base Handler is an optional class where you can put the boilerplate code that’s common to all handler classes.

Usually, this class defines a field for storing a reference to the next handler. The clients can build a chain by passing a handler to the constructor or setter of the previous handler. The class may also implement the default handling behavior: it can pass execution to the next handler after checking for its existence.

-

Concrete Handlers contain the actual code for processing requests. Upon receiving a request, each handler must decide whether to process it and, additionally, whether to pass it along the chain.

Handlers are usually self-contained and immutable, accepting all necessary data just once via the constructor.

-

The Client may compose chains just once or compose them dynamically, depending on the application’s logic. Note that a request can be sent to any handler in the chain—it doesn’t have to be the first one.

Pseudocode

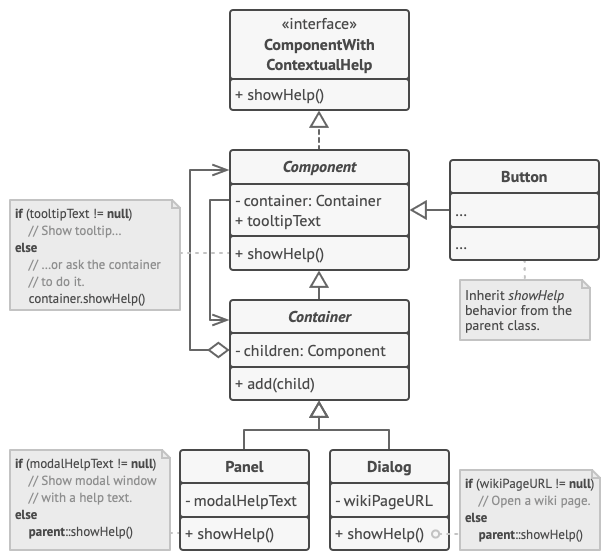

In this example, the Chain of Responsibility pattern is responsible for displaying contextual help information for active GUI elements.

The GUI classes are built with the Composite pattern. Each element is linked to its container element. At any point, you can build a chain of elements that starts with the element itself and goes through all of its container elements.

The application’s GUI is usually structured as an object tree. For example, the Dialog class, which renders the main window of the app, would be the root of the object tree. The dialog contains Panels, which might contain other panels or simple low-level elements like Buttons and TextFields.

A simple component can show brief contextual tooltips, as long as the component has some help text assigned. But more complex components define their own way of showing contextual help, such as showing an excerpt from the manual or opening a page in a browser.

That’s how a help request traverses GUI objects.

When a user points the mouse cursor at an element and presses the F1 key, the application detects the component under the pointer and sends it a help request. The request bubbles up through all the element’s containers until it reaches the element that’s capable of displaying the help information.

// The handler interface declares a method for executing a

// request.

interface ComponentWithContextualHelp is

method showHelp()

// The base class for simple components.

abstract class Component implements ComponentWithContextualHelp is

field tooltipText: string

// The component's container acts as the next link in the

// chain of handlers.

protected field container: Container

// The component shows a tooltip if there's help text

// assigned to it. Otherwise it forwards the call to the

// container, if it exists.

method showHelp() is

if (tooltipText != null)

// Show tooltip.

else

container.showHelp()

// Containers can contain both simple components and other

// containers as children. The chain relationships are

// established here. The class inherits showHelp behavior from

// its parent.

abstract class Container extends Component is

protected field children: array of Component

method add(child) is

children.add(child)

child.container = this

// Primitive components may be fine with default help

// implementation...

class Button extends Component is

// ...

// But complex components may override the default

// implementation. If the help text can't be provided in a new

// way, the component can always call the base implementation

// (see Component class).

class Panel extends Container is

field modalHelpText: string

method showHelp() is

if (modalHelpText != null)

// Show a modal window with the help text.

else

super.showHelp()

// ...same as above...

class Dialog extends Container is

field wikiPageURL: string

method showHelp() is

if (wikiPageURL != null)

// Open the wiki help page.

else

super.showHelp()

// Client code.

class Application is

// Every application configures the chain differently.

method createUI() is

dialog = new Dialog("Budget Reports")

dialog.wikiPageURL = "http://..."

panel = new Panel(0, 0, 400, 800)

panel.modalHelpText = "This panel does..."

ok = new Button(250, 760, 50, 20, "OK")

ok.tooltipText = "This is an OK button that..."

cancel = new Button(320, 760, 50, 20, "Cancel")

// ...

panel.add(ok)

panel.add(cancel)

dialog.add(panel)

// Imagine what happens here.

method onF1KeyPress() is

component = this.getComponentAtMouseCoords()

component.showHelp()

Applicability

Use the Chain of Responsibility pattern when your program is expected to process different kinds of requests in various ways, but the exact types of requests and their sequences are unknown beforehand.

The pattern lets you link several handlers into one chain and, upon receiving a request, “ask” each handler whether it can process it. This way all handlers get a chance to process the request.

Use the pattern when it’s essential to execute several handlers in a particular order.

Since you can link the handlers in the chain in any order, all requests will get through the chain exactly as you planned.

Use the CoR pattern when the set of handlers and their order are supposed to change at runtime.

If you provide setters for a reference field inside the handler classes, you’ll be able to insert, remove or reorder handlers dynamically.

How to Implement

-

Declare the handler interface and describe the signature of a method for handling requests.

Decide how the client will pass the request data into the method. The most flexible way is to convert the request into an object and pass it to the handling method as an argument.

-

To eliminate duplicate boilerplate code in concrete handlers, it might be worth creating an abstract base handler class, derived from the handler interface.

This class should have a field for storing a reference to the next handler in the chain. Consider making the class immutable. However, if you plan to modify chains at runtime, you need to define a setter for altering the value of the reference field.

You can also implement the convenient default behavior for the handling method, which is to forward the request to the next object unless there’s none left. Concrete handlers will be able to use this behavior by calling the parent method.

-

One by one create concrete handler subclasses and implement their handling methods. Each handler should make two decisions when receiving a request:

- Whether it’ll process the request.

- Whether it’ll pass the request along the chain.

-

The client may either assemble chains on its own or receive pre-built chains from other objects. In the latter case, you must implement some factory classes to build chains according to the configuration or environment settings.

-

The client may trigger any handler in the chain, not just the first one. The request will be passed along the chain until some handler refuses to pass it further or until it reaches the end of the chain.

-

Due to the dynamic nature of the chain, the client should be ready to handle the following scenarios:

- The chain may consist of a single link.

- Some requests may not reach the end of the chain.

- Others may reach the end of the chain unhandled.

Pros and Cons

- You can control the order of request handling.

- Single Responsibility Principle. You can decouple classes that invoke operations from classes that perform operations.

- Open/Closed Principle. You can introduce new handlers into the app without breaking the existing client code.

- Some requests may end up unhandled.

Relations with Other Patterns

-

Chain of Responsibility, Command, Mediator and Observer address various ways of connecting senders and receivers of requests:

- Chain of Responsibility passes a request sequentially along a dynamic chain of potential receivers until one of them handles it.

- Command establishes unidirectional connections between senders and receivers.

- Mediator eliminates direct connections between senders and receivers, forcing them to communicate indirectly via a mediator object.

- Observer lets receivers dynamically subscribe to and unsubscribe from receiving requests.

-

Chain of Responsibility is often used in conjunction with Composite. In this case, when a leaf component gets a request, it may pass it through the chain of all of the parent components down to the root of the object tree.

-

Handlers in Chain of Responsibility can be implemented as Commands. In this case, you can execute a lot of different operations over the same context object, represented by a request.

However, there’s another approach, where the request itself is a Command object. In this case, you can execute the same operation in a series of different contexts linked into a chain.

-

Chain of Responsibility and Decorator have very similar class structures. Both patterns rely on recursive composition to pass the execution through a series of objects. However, there are several crucial differences.

The CoR handlers can execute arbitrary operations independently of each other. They can also stop passing the request further at any point. On the other hand, various Decorators can extend the object’s behavior while keeping it consistent with the base interface. In addition, decorators aren’t allowed to break the flow of the request.