Bridge

Intent

Bridge is a structural design pattern that lets you split a large class or a set of closely related classes into two separate hierarchies—abstraction and implementation—which can be developed independently of each other.

Problem

Abstraction? Implementation? Sound scary? Stay calm and let’s consider a simple example.

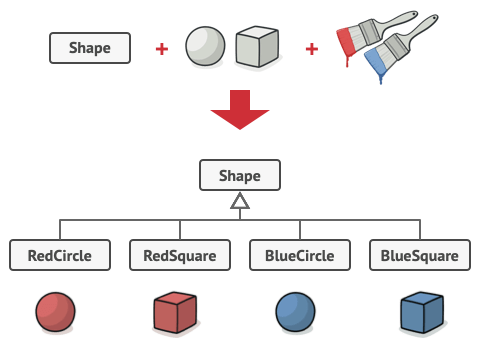

Say you have a geometric Shape class with a pair of subclasses: Circle and Square. You want to extend this class hierarchy to incorporate colors, so you plan to create Red and Blue shape subclasses. However, since you already have two subclasses, you’ll need to create four class combinations such as BlueCircle and RedSquare.

Number of class combinations grows in geometric progression.

Adding new shape types and colors to the hierarchy will grow it exponentially. For example, to add a triangle shape you’d need to introduce two subclasses, one for each color. And after that, adding a new color would require creating three subclasses, one for each shape type. The further we go, the worse it becomes.

Solution

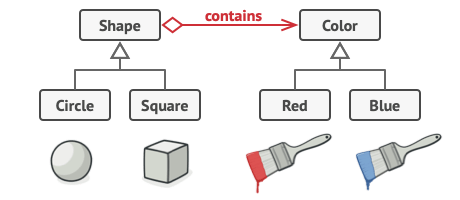

This problem occurs because we’re trying to extend the shape classes in two independent dimensions: by form and by color. That’s a very common issue with class inheritance.

The Bridge pattern attempts to solve this problem by switching from inheritance to the object composition. What this means is that you extract one of the dimensions into a separate class hierarchy, so that the original classes will reference an object of the new hierarchy, instead of having all of its state and behaviors within one class.

You can prevent the explosion of a class hierarchy by transforming it into several related hierarchies.

Following this approach, we can extract the color-related code into its own class with two subclasses: Red and Blue. The Shape class then gets a reference field pointing to one of the color objects. Now the shape can delegate any color-related work to the linked color object. That reference will act as a bridge between the Shape and Color classes. From now on, adding new colors won’t require changing the shape hierarchy, and vice versa.

Abstraction and Implementation

The GoF book introduces the terms Abstraction and Implementation as part of the Bridge definition. In my opinion, the terms sound too academic and make the pattern seem more complicated than it really is. Having read the simple example with shapes and colors, let’s decipher the meaning behind the GoF book’s scary words.

Abstraction (also called interface) is a high-level control layer for some entity. This layer isn’t supposed to do any real work on its own. It should delegate the work to the implementation layer (also called platform).

Note that we’re not talking about interfaces or abstract classes from your programming language. These aren’t the same things.

When talking about real applications, the abstraction can be represented by a graphical user interface (GUI), and the implementation could be the underlying operating system code (API) which the GUI layer calls in response to user interactions.

Generally speaking, you can extend such an app in two independent directions:

- Have several different GUIs (for instance, tailored for regular customers or admins).

- Support several different APIs (for example, to be able to launch the app under Windows, Linux, and macOS).

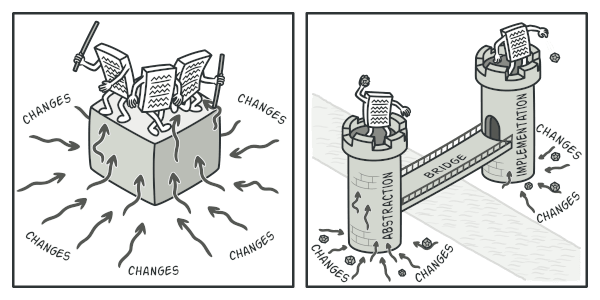

In a worst-case scenario, this app might look like a giant spaghetti bowl, where hundreds of conditionals connect different types of GUI with various APIs all over the code.

Making even a simple change to a monolithic codebase is pretty hard because you must understand the entire thing very well. Making changes to smaller, well-defined modules is much easier.

You can bring order to this chaos by extracting the code related to specific interface-platform combinations into separate classes. However, soon you’ll discover that there are lots of these classes. The class hierarchy will grow exponentially because adding a new GUI or supporting a different API would require creating more and more classes.

Let’s try to solve this issue with the Bridge pattern. It suggests that we divide the classes into two hierarchies:

- Abstraction: the GUI layer of the app.

- Implementation: the operating systems’ APIs.

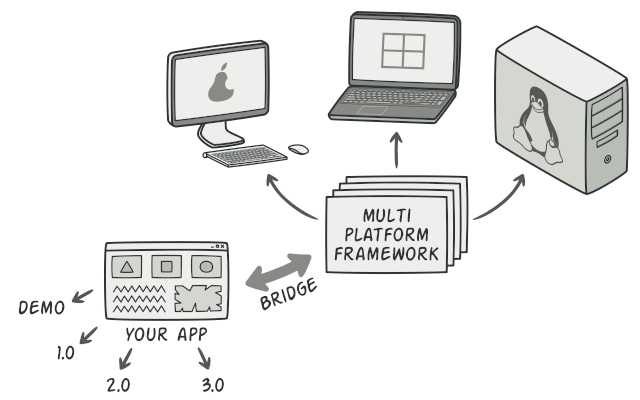

One of the ways to structure a cross-platform application.

The abstraction object controls the appearance of the app, delegating the actual work to the linked implementation object. Different implementations are interchangeable as long as they follow a common interface, enabling the same GUI to work under Windows and Linux.

As a result, you can change the GUI classes without touching the API-related classes. Moreover, adding support for another operating system only requires creating a subclass in the implementation hierarchy.

Structure

-

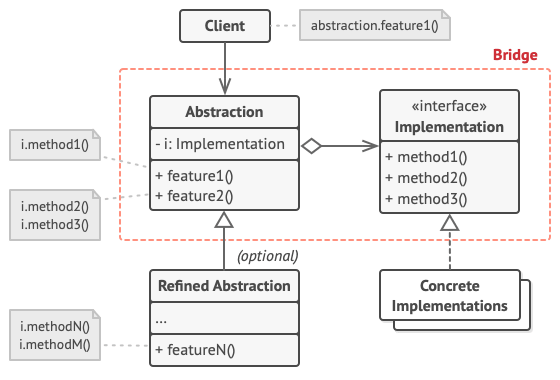

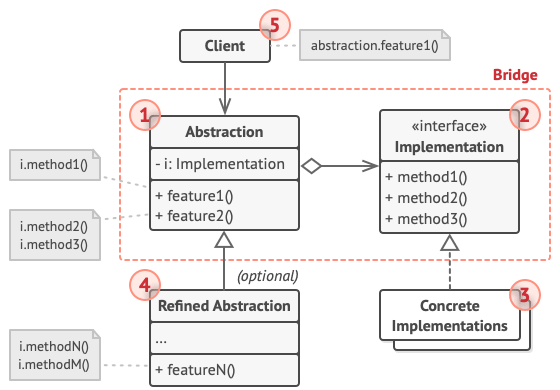

The Abstraction provides high-level control logic. It relies on the implementation object to do the actual low-level work.

-

The Implementation declares the interface that’s common for all concrete implementations. An abstraction can only communicate with an implementation object via methods that are declared here.

The abstraction may list the same methods as the implementation, but usually the abstraction declares some complex behaviors that rely on a wide variety of primitive operations declared by the implementation.

-

Concrete Implementations contain platform-specific code.

-

Refined Abstractions provide variants of control logic. Like their parent, they work with different implementations via the general implementation interface.

-

Usually, the Client is only interested in working with the abstraction. However, it’s the client’s job to link the abstraction object with one of the implementation objects.

Pseudocode

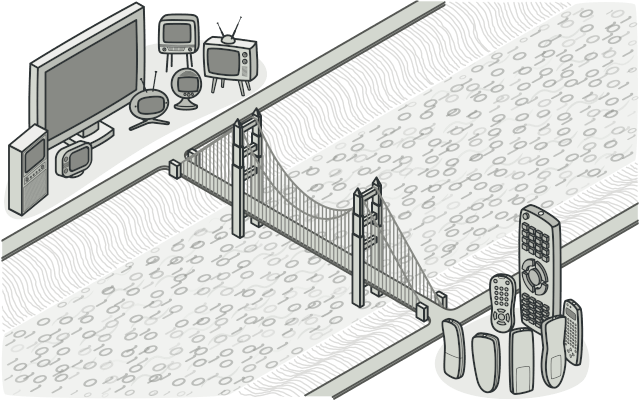

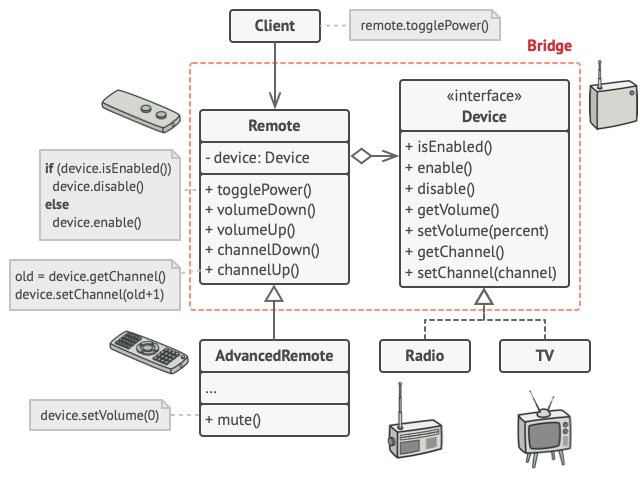

This example illustrates how the Bridge pattern can help divide the monolithic code of an app that manages devices and their remote controls. The Device classes act as the implementation, whereas the Remotes act as the abstraction.

The original class hierarchy is divided into two parts: devices and remote controls.

The base remote control class declares a reference field that links it with a device object. All remotes work with the devices via the general device interface, which lets the same remote support multiple device types.

You can develop the remote control classes independently from the device classes. All that’s needed is to create a new remote subclass. For example, a basic remote control might only have two buttons, but you could extend it with additional features, such as an extra battery or a touchscreen.

The client code links the desired type of remote control with a specific device object via the remote’s constructor.

// The "abstraction" defines the interface for the "control"

// part of the two class hierarchies. It maintains a reference

// to an object of the "implementation" hierarchy and delegates

// all of the real work to this object.

class RemoteControl is

protected field device: Device

constructor RemoteControl(device: Device) is

this.device = device

method togglePower() is

if (device.isEnabled()) then

device.disable()

else

device.enable()

method volumeDown() is

device.setVolume(device.getVolume() - 10)

method volumeUp() is

device.setVolume(device.getVolume() + 10)

method channelDown() is

device.setChannel(device.getChannel() - 1)

method channelUp() is

device.setChannel(device.getChannel() + 1)

// You can extend classes from the abstraction hierarchy

// independently from device classes.

class AdvancedRemoteControl extends RemoteControl is

method mute() is

device.setVolume(0)

// The "implementation" interface declares methods common to all

// concrete implementation classes. It doesn't have to match the

// abstraction's interface. In fact, the two interfaces can be

// entirely different. Typically the implementation interface

// provides only primitive operations, while the abstraction

// defines higher-level operations based on those primitives.

interface Device is

method isEnabled()

method enable()

method disable()

method getVolume()

method setVolume(percent)

method getChannel()

method setChannel(channel)

// All devices follow the same interface.

class Tv implements Device is

// ...

class Radio implements Device is

// ...

// Somewhere in client code.

tv = new Tv()

remote = new RemoteControl(tv)

remote.togglePower()

radio = new Radio()

remote = new AdvancedRemoteControl(radio)

Applicability

Use the Bridge pattern when you want to divide and organize a monolithic class that has several variants of some functionality (for example, if the class can work with various database servers).

The bigger a class becomes, the harder it is to figure out how it works, and the longer it takes to make a change. The changes made to one of the variations of functionality may require making changes across the whole class, which often results in making errors or not addressing some critical side effects.

The Bridge pattern lets you split the monolithic class into several class hierarchies. After this, you can change the classes in each hierarchy independently of the classes in the others. This approach simplifies code maintenance and minimizes the risk of breaking existing code.

Use the pattern when you need to extend a class in several orthogonal (independent) dimensions.

The Bridge suggests that you extract a separate class hierarchy for each of the dimensions. The original class delegates the related work to the objects belonging to those hierarchies instead of doing everything on its own.

Use the Bridge if you need to be able to switch implementations at runtime.

Although it’s optional, the Bridge pattern lets you replace the implementation object inside the abstraction. It’s as easy as assigning a new value to a field.

By the way, this last item is the main reason why so many people confuse the Bridge with the Strategy pattern. Remember that a pattern is more than just a certain way to structure your classes. It may also communicate intent and a problem being addressed.

How to Implement

-

Identify the orthogonal dimensions in your classes. These independent concepts could be: abstraction/platform, domain/infrastructure, front-end/back-end, or interface/implementation.

-

See what operations the client needs and define them in the base abstraction class.

-

Determine the operations available on all platforms. Declare the ones that the abstraction needs in the general implementation interface.

-

For all platforms in your domain create concrete implementation classes, but make sure they all follow the implementation interface.

-

Inside the abstraction class, add a reference field for the implementation type. The abstraction delegates most of the work to the implementation object that’s referenced in that field.

-

If you have several variants of high-level logic, create refined abstractions for each variant by extending the base abstraction class.

-

The client code should pass an implementation object to the abstraction’s constructor to associate one with the other. After that, the client can forget about the implementation and work only with the abstraction object.

Pros and Cons

- You can create platform-independent classes and apps.

- The client code works with high-level abstractions. It isn’t exposed to the platform details.

- Open/Closed Principle. You can introduce new abstractions and implementations independently from each other.

- Single Responsibility Principle. You can focus on high-level logic in the abstraction and on platform details in the implementation.

- You might make the code more complicated by applying the pattern to a highly cohesive class.

Relations with Other Patterns

-

Bridge is usually designed up-front, letting you develop parts of an application independently of each other. On the other hand, Adapter is commonly used with an existing app to make some otherwise-incompatible classes work together nicely.

-

Bridge, State, Strategy (and to some degree Adapter) have very similar structures. Indeed, all of these patterns are based on composition, which is delegating work to other objects. However, they all solve different problems. A pattern isn’t just a recipe for structuring your code in a specific way. It can also communicate to other developers the problem the pattern solves.

-

You can use Abstract Factory along with Bridge. This pairing is useful when some abstractions defined by Bridge can only work with specific implementations. In this case, Abstract Factory can encapsulate these relations and hide the complexity from the client code.

-

You can combine Builder with Bridge: the director class plays the role of the abstraction, while different builders act as implementations.