Strategy

Intent

Strategy is a behavioral design pattern that lets you define a family of algorithms, put each of them into a separate class, and make their objects interchangeable.

Problem

One day you decided to create a navigation app for casual travelers. The app was centered around a beautiful map which helped users quickly orient themselves in any city.

One of the most requested features for the app was automatic route planning. A user should be able to enter an address and see the fastest route to that destination displayed on the map.

The first version of the app could only build the routes over roads. People who traveled by car were bursting with joy. But apparently, not everybody likes to drive on their vacation. So with the next update, you added an option to build walking routes. Right after that, you added another option to let people use public transport in their routes.

However, that was only the beginning. Later you planned to add route building for cyclists. And even later, another option for building routes through all of a city’s tourist attractions.

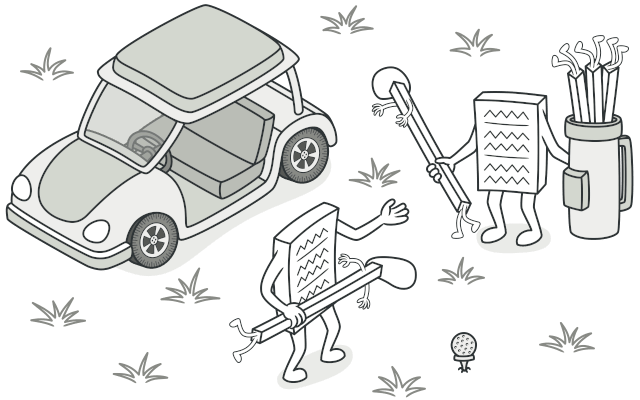

The code of the navigator became bloated.

While from a business perspective the app was a success, the technical part caused you many headaches. Each time you added a new routing algorithm, the main class of the navigator doubled in size. At some point, the beast became too hard to maintain.

Any change to one of the algorithms, whether it was a simple bug fix or a slight adjustment of the street score, affected the whole class, increasing the chance of creating an error in already-working code.

In addition, teamwork became inefficient. Your teammates, who had been hired right after the successful release, complain that they spend too much time resolving merge conflicts. Implementing a new feature requires you to change the same huge class, conflicting with the code produced by other people.

Solution

The Strategy pattern suggests that you take a class that does something specific in a lot of different ways and extract all of these algorithms into separate classes called strategies.

The original class, called context, must have a field for storing a reference to one of the strategies. The context delegates the work to a linked strategy object instead of executing it on its own.

The context isn’t responsible for selecting an appropriate algorithm for the job. Instead, the client passes the desired strategy to the context. In fact, the context doesn’t know much about strategies. It works with all strategies through the same generic interface, which only exposes a single method for triggering the algorithm encapsulated within the selected strategy.

This way the context becomes independent of concrete strategies, so you can add new algorithms or modify existing ones without changing the code of the context or other strategies.

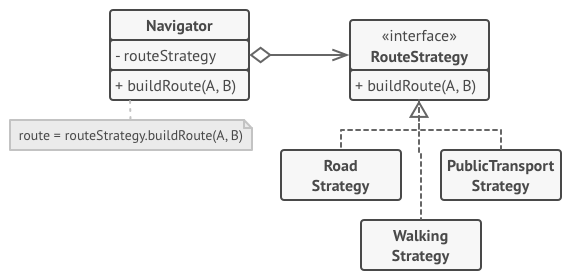

Route planning strategies.

In our navigation app, each routing algorithm can be extracted to its own class with a single buildRoute method. The method accepts an origin and destination and returns a collection of the route’s checkpoints.

Even though given the same arguments, each routing class might build a different route, the main navigator class doesn’t really care which algorithm is selected since its primary job is to render a set of checkpoints on the map. The class has a method for switching the active routing strategy, so its clients, such as the buttons in the user interface, can replace the currently selected routing behavior with another one.

Real-World Analogy

Various strategies for getting to the airport.

Imagine that you have to get to the airport. You can catch a bus, order a cab, or get on your bicycle. These are your transportation strategies. You can pick one of the strategies depending on factors such as budget or time constraints.

Structure

-

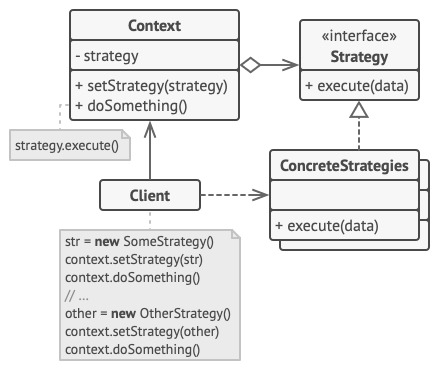

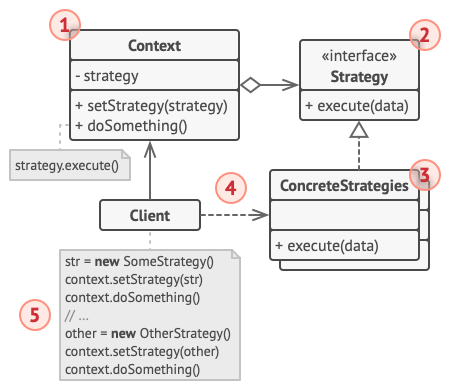

The Context maintains a reference to one of the concrete strategies and communicates with this object only via the strategy interface.

-

The Strategy interface is common to all concrete strategies. It declares a method the context uses to execute a strategy.

-

Concrete Strategies implement different variations of an algorithm the context uses.

-

The context calls the execution method on the linked strategy object each time it needs to run the algorithm. The context doesn’t know what type of strategy it works with or how the algorithm is executed.

-

The Client creates a specific strategy object and passes it to the context. The context exposes a setter which lets clients replace the strategy associated with the context at runtime.

Pseudocode

In this example, the context uses multiple strategies to execute various arithmetic operations.

// The strategy interface declares operations common to all

// supported versions of some algorithm. The context uses this

// interface to call the algorithm defined by the concrete

// strategies.

interface Strategy is

method execute(a, b)

// Concrete strategies implement the algorithm while following

// the base strategy interface. The interface makes them

// interchangeable in the context.

class ConcreteStrategyAdd implements Strategy is

method execute(a, b) is

return a + b

class ConcreteStrategySubtract implements Strategy is

method execute(a, b) is

return a - b

class ConcreteStrategyMultiply implements Strategy is

method execute(a, b) is

return a * b

// The context defines the interface of interest to clients.

class Context is

// The context maintains a reference to one of the strategy

// objects. The context doesn't know the concrete class of a

// strategy. It should work with all strategies via the

// strategy interface.

private strategy: Strategy

// Usually the context accepts a strategy through the

// constructor, and also provides a setter so that the

// strategy can be switched at runtime.

method setStrategy(Strategy strategy) is

this.strategy = strategy

// The context delegates some work to the strategy object

// instead of implementing multiple versions of the

// algorithm on its own.

method executeStrategy(int a, int b) is

return strategy.execute(a, b)

// The client code picks a concrete strategy and passes it to

// the context. The client should be aware of the differences

// between strategies in order to make the right choice.

class ExampleApplication is

method main() is

Create context object.

Read first number.

Read last number.

Read the desired action from user input.

if (action == addition) then

context.setStrategy(new ConcreteStrategyAdd())

if (action == subtraction) then

context.setStrategy(new ConcreteStrategySubtract())

if (action == multiplication) then

context.setStrategy(new ConcreteStrategyMultiply())

result = context.executeStrategy(First number, Second number)

Print result.

Applicability

Use the Strategy pattern when you want to use different variants of an algorithm within an object and be able to switch from one algorithm to another during runtime.

The Strategy pattern lets you indirectly alter the object’s behavior at runtime by associating it with different sub-objects which can perform specific sub-tasks in different ways.

Use the Strategy when you have a lot of similar classes that only differ in the way they execute some behavior.

The Strategy pattern lets you extract the varying behavior into a separate class hierarchy and combine the original classes into one, thereby reducing duplicate code.

Use the pattern to isolate the business logic of a class from the implementation details of algorithms that may not be as important in the context of that logic.

The Strategy pattern lets you isolate the code, internal data, and dependencies of various algorithms from the rest of the code. Various clients get a simple interface to execute the algorithms and switch them at runtime.

Use the pattern when your class has a massive conditional statement that switches between different variants of the same algorithm.

The Strategy pattern lets you do away with such a conditional by extracting all algorithms into separate classes, all of which implement the same interface. The original object delegates execution to one of these objects, instead of implementing all variants of the algorithm.

How to Implement

-

In the context class, identify an algorithm that’s prone to frequent changes. It may also be a massive conditional that selects and executes a variant of the same algorithm at runtime.

-

Declare the strategy interface common to all variants of the algorithm.

-

One by one, extract all algorithms into their own classes. They should all implement the strategy interface.

-

In the context class, add a field for storing a reference to a strategy object. Provide a setter for replacing values of that field. The context should work with the strategy object only via the strategy interface. The context may define an interface which lets the strategy access its data.

-

Clients of the context must associate it with a suitable strategy that matches the way they expect the context to perform its primary job.

Pros and Cons

- You can swap algorithms used inside an object at runtime.

- You can isolate the implementation details of an algorithm from the code that uses it.

- You can replace inheritance with composition.

- Open/Closed Principle. You can introduce new strategies without having to change the context.

- If you only have a couple of algorithms and they rarely change, there’s no real reason to overcomplicate the program with new classes and interfaces that come along with the pattern.

- Clients must be aware of the differences between strategies to be able to select a proper one.

- A lot of modern programming languages have functional type support that lets you implement different versions of an algorithm inside a set of anonymous functions. Then you could use these functions exactly as you’d have used the strategy objects, but without bloating your code with extra classes and interfaces.

Relations with Other Patterns

-

Bridge, State, Strategy (and to some degree Adapter) have very similar structures. Indeed, all of these patterns are based on composition, which is delegating work to other objects. However, they all solve different problems. A pattern isn’t just a recipe for structuring your code in a specific way. It can also communicate to other developers the problem the pattern solves.

-

Command and Strategy may look similar because you can use both to parameterize an object with some action. However, they have very different intents.

-

You can use Command to convert any operation into an object. The operation’s parameters become fields of that object. The conversion lets you defer execution of the operation, queue it, store the history of commands, send commands to remote services, etc.

-

On the other hand, Strategy usually describes different ways of doing the same thing, letting you swap these algorithms within a single context class.

-

-

Decorator lets you change the skin of an object, while Strategy lets you change the guts.

-

Template Method is based on inheritance: it lets you alter parts of an algorithm by extending those parts in subclasses. Strategy is based on composition: you can alter parts of the object’s behavior by supplying it with different strategies that correspond to that behavior. Template Method works at the class level, so it’s static. Strategy works on the object level, letting you switch behaviors at runtime.

-

State can be considered as an extension of Strategy. Both patterns are based on composition: they change the behavior of the context by delegating some work to helper objects. Strategy makes these objects completely independent and unaware of each other. However, State doesn’t restrict dependencies between concrete states, letting them alter the state of the context at will.